Break the Cycle

Latin American photobooks and the audience

The author sows, the reading fertilizes. Giannetti, Eduardo. 2016. ‘Perante o leitor [Before the reader]’. In Trópicos Utópicos [Utopian Tropics]. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras.

Photobooks have been the engine of exciting experiments in the book medium for the last fifteen years. We’ve never before had such a variety of titles circulating the globe, yet we’re witnessing a saturation point. To blame the confrontation between print and online is misleading. Books should actually thank the Internet for intriguing potential, faraway readers before swooping in with their physical presence.

It’s this very physical, intimate, two-way relationship that readers seek in tandem with the need to take a break from this hyper-connected world and escape the palimpsest of their lives by diving into a narrative, something they feel they can be a part of, or at least relate to. This is the best impact we can ask of a book, but photobooks struggle to achieve it on a larger scale.

The conditions necessary for increasing their outreach are out there waiting, above all the visual literacy of the ‘latent’ audience, which is significantly higher than just a few decades ago. To name a close and successful example, comics have been both contributing to and benefitting from this visual turn, constantly growing their circulation while offering, besides classic superhero titles, increasingly literary and experimental graphic novels.

Tagging the audience as ‘latent’ is not arbitrary: people with interests other than photography are likely to enjoy photobooks once they get to know them, but are they really offered this opportunity? A bubbly publishing ecosystem together with specialised events and fairs are spreading the word, yet those answering the call are normally already part of the photography scene, probably with a dummy to publish. No matter if it’s the centre or the periphery of the cultural world, endogamy is what joins both under the same sword of Damocles: the future of photobooks has to be increasingly outside the photography cosmos, or there won’t be any future at all.

Walter Costa

05 nov. 2019 • 10 min

©Panchoaga, Jorge, Dulce y Salada [Seet and Salty]. Bogotá: Croma. 2018

©Estol, Federico, Héroes del Brillo. 2018

©Weinstein, Luis, Es lo que Hay. Santiago: Cenfoto. 2014-2018

© Goldenberg, Tamara; Perosa, Martina, Mamarazzi. Buenos Aires: Frente Editorial Abierto. 2018

© Goldenberg, Tamara; Perosa, Martina, Mamarazzi being read in a hairdresser shop in Buenos Aires

© Pani, Sebastián; Grosso, Belén, Y un Día el Fuego. Buenos Aires: Turma. 2018

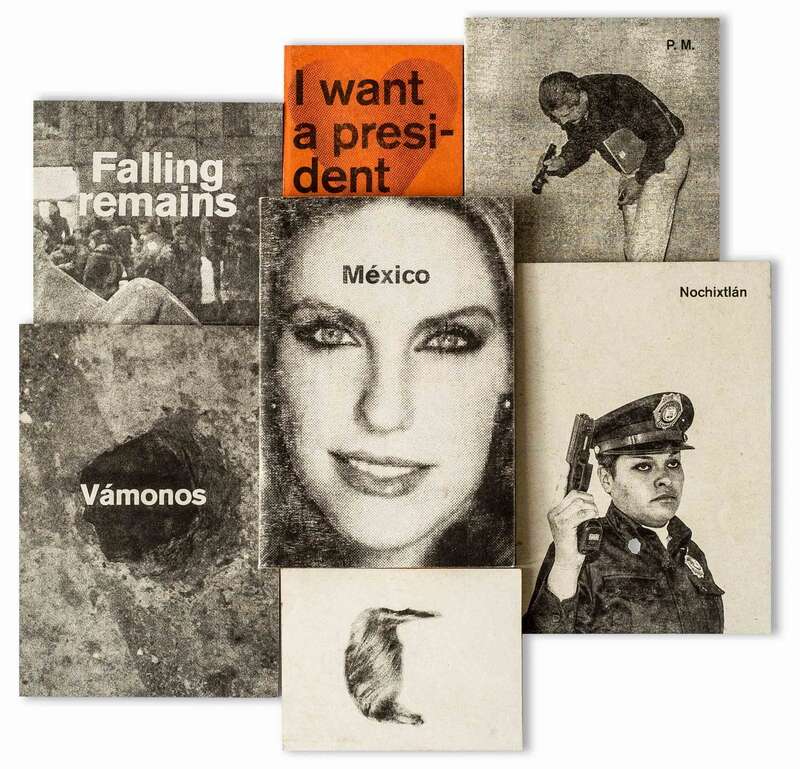

Some titles from publishing house Gato Negro

Walter Costa constructed a manifesto about the future of Latin-American photobooks. It sums up the discussions that took place last March 2019 during the enCMYK Photobook Festival Costa curated for the Montevideo Center of Photography.

Latin America is relegated to the cultural periphery, meaning there are far fewer resources available and it has serious difficulties making its cultural production circulate within and outside its boundaries.This is a problem that was already pointed out back in 1981 by Guatemalan photographer and publisher María Cristina Orive, who conducted the first ever research on photography books published on the continent:Hecho en Latinoamérica. Libros Fotográficos de Autores Latinoamericanos [Made in Latin America. Photography Books from Latin American Authors], published and exhibited in occasion of the second Coloquio Latinoamericano de Fotografía [Latin American Photography Colloquium] held in Mexico City. She came to three final conclusions. The first: nobody knows what’s been done, even in their own countries. The second: there are photographers who paid for the publishing of their work. No doubt they think that once created and printed, the book will reach the reader because of its inherent value. The third: in many countries, books have been paid for by a company, an institution or a government. They’re objects of prestige (like culture!), and unfortunately, they never reach an interested audience. Continental networks have indeed risen in the recent decades; nevertheless, knowing what’s happening in a neighbouring country can still be hard. Big cities, where most culture-makers and audiences concentrate, are awfully far from each other, with loose or expensive connections. Great socioeconomic inequalities maintain a classism interwoven with racism, making minorities shamefully underrepresented on the makers’ sideIt’s interesting to look at the survey done before the Encontro de Publicadores(Publishers’ Meeting) that took place in São Paulo in 2016. Considering that out of 310 replies, 80 percent were Brazilians, 68 percent of the total defined themselves as White. VVAA. 2016. Entre, à maneira de, junto a publicadores [Between, the way, together with publishers]. São Paulo: Tenda de Livros; Edições Aurora; Zerocentos Publicações. Survey booklet, 2. Also available at https://docs.google.com/document/d/1GkZBagupVauwRaavUCJo8maOUKdg2v3BKaDQkywbBTA/edit?usp=sharing but overrepresented in the works that circulate, raising urgent issues of inclusiveness and ‘speech positioning'This is a term from critical race theory brought to current public discourse by Brazilian political philosopher Djamila Ribeiro. It refers to the privilege of talking in racist and patriarchal societies, where the legitimised discourse is that of White heterosexual men. It reveals how different voices are considered as ‘others’ and how this regime of discursive authorisation prevents those considered as ‘others’ from exercising the right to make their voices heard. .

An added difficulty fostered by this peripheral status is described by Chilean photographer and curator Luis Weinstein. He noted that on one hand, more and more pictures are made in Latin America, and on the other, the big market for these images is located in other, richer territories. That imbalance establishes a cultural vector that drives many authors to generate and circulate works that affirm a local exoticism—commercially more successful—that fits into a view built over centuries from the cultural hegemony of the capitalist, Christian, White and wealthy West.Weinstein, Luis. 2018. ‘Sobre la circulación y distribución de nuestra fotografía [On circulation and distribution of our photography]’. In Sur - Revista de Fotolibros Latinoamericanos [South – Latin American Photobooks Magazine] 1, edited by Villaro, Leandro. 3. Buenos Aires: FOLA Fototeca Latinoamericana; Caracas: La Cueva Editorial. The situation is changing, but the legitimation that comes from being recognised by the centre nevertheless keeps tempting local authors to please the distant over the local.

This mismatch is connected to an original sin that needs to be faced. Brazilian critic and professor Ronaldo Entler nailed it when he wrote that there’s a certain contradiction in our discourses celebrating the photobook: we value this format for its capacity to circulate, but we still want to collect them like artworks sold by art galleries. In doing so, we fail to let books be consumed in a less solemn way by a broader and less specialised public.Entler, Ronaldo. 2019.‘Notas sobre o atrito entre o livro e a fotografia [Notes on the friction between book and photography]’. Zum Revista de Fotografia [Zum Photography Magazine].revistazum.com.br/en/colunistas/livro-e-a-fotografia Solemnity is exclusivity, that is, self-referentiality, which is, again, endogamy—a self-imposed standing point around which a vicious circle keeps wheeling, delimiting an artsy comfort zone whose size tells it all about the lack of ability—or willingness—to actively increase photobooks’ outreach.

But fresh energy is coming from the Latin American authors and publishers who face these challenges. In this context, continental venues and fairs come into play not as extensions of the same old comfort zone but as spaces to discuss ideas and practices aimed at engaging with broader audiences. The manifesto drawn up during the sixth EnCMYK Encontro de Fotolibros (Photobook Meeting) — a biannual festival organised by the Montevideo Center of Photography (CdF) — lists some bold cues to work on more sustainable, accessible and rebellious photobooks.Costa, Walter. 2019. Walter Costa. https://waltercosta.site/writing/

Against selfish publishing

When it’s all about having one’s name on the cover, there’s little room for anything but the author’s ego, let alone the reader; the same goes for the ‘author/dictator’ who wants the book to be interpreted in only one way. A good antidote is to always keep in mind what writer Steven Pressfield said: ‘Nobody wants to read your shit.Pressfield, Steven. 2009. ‘The Most Important Writing Lesson I Ever Learned.’ Steven Pressfield (blog). stevenpressfield.com/2009/10/writing-wednesdays-2-the-most-important-writing-lession-i-ever-learned His statement brutally points out that publishing is above all a transaction based on a much-coveted commodity nowadays: attention. What do we give in exchange for the time and money donated by busy people who also happen to be readers? Pressfield gives a couple of tips: ‘Reduce your message to its simplest, clearest, easiest-to-understand form’ and ‘Make it fun. Or sexy or interesting or informative'.Ibid. Somebody could argue that this equates to a loss of purity, but isn’t empathy with readers the only possible starting point to getting out of the circle?

(Not) Everything exists in order to end up as a (photo)book

The mantra that once said you must have a nicely printed portfolio if you want to be a respected author now states that you need a photobook. But the formats are incomparable both in terms of purpose and investment. Dutch artist and publisher Erik van der Weijde affirms in his publishing manifesto: ‘Each published title must add value to the existing ones. ... All books that are not made are, at least, just as important'.Weijde, Erik van der. 2017. This Is Not My Book. 16-17. Leipzig: Spector Books. If after studying, testing and collaborating, you realise that a photobook is not the answer, more creative energy will be available to translate the project into other formats, without contributing to the above saturation. Colombian author and publisher Jorge Panchoaga realised that the best way to present Dulce y Salada (Sweet and Salty)—a project about a fishing village at the mouth of the Magdalena River—was to make both a photobook and interactive multimedia.Panchoaga, Jorge. 2018. Dulce y Salada. http://www.dulceysalada.com/ Tuning the contents according to the strengths and limitations of each medium, both were benefited by cross-references and synergies.

Break the cycle

There are radical actions that can make photobooks more accessible to audiences beyond the fans of independent publishing. Brazilian publisher and researcher Fernanda Grigolin, with her project Tenda de Livros (Book Tent), brought affordable photobooks, artist books and poetry to an open-air Sunday market in São Paulo throughout 2014.Grigolin, Fernanda. 2014. Tenda de Livros. https://tendadelivros.org/historia/ Between clothes and food, solemnity was soundly stripped down, bringing near many people who’d never flipped through a photobook before. Uruguayan photographer Federico Estol developed a project with a group of shoe-shiners in La Paz, Bolivia, creating Héroes del Brillo (Shine Heroes).Estol, Federico. 2019. Heroes del Brillo. Uploaded 2019. https://vimeo.com/302063565 He chose to co-publish it as a supplement to the group’s newspaper, offered to clients and passers-by to fund their activities. It’s an ‘artivist’ strategy that, besides empowering the protagonists of the project, reached local audiences through an already established distribution network without impeding the publication’s ability to circulate within the photobook world as well.

Charge less, buy more

When even loyal readers are complaining about prices, making photobooks accessible to less specialised audiences necessarily means making them affordable too. Latin American resiliency in the face of limited resources and high production costs fosters creative achievements with little support; another factor is that the market isn’t wealthy enough for making photobooks just for collectors a viable choice. Weinstein’s project Es lo Que Hay (That’s the Way Things Are)The four titles (Esto ha sido [This Has Been], Se vende ilusiones [Illusions for Sale], Apuntes del Edén [Eden Notes], Toque de queda [Curfew]) can be found here http://www.luisweinstein.com/ is based on his archive of pictures taken during the years of Augusto Pinochet’s dictatorship. He wanted to focus on narrative and budget so, in collaboration with designer Carolina Zañartu between 2014 and 2018, he published four thin and affordable books as independent chapters of a whole. The only wink at collectors is a cardboard cover to house them together.

The reader is your shepherd

Readers are always way smarter than we think, yet it’s easy to fall into ‘I-want-you-to-consume-what-I-do’ attitudes. How can we tune our message better and be more reader-friendly, avoiding underestimation and imposition? The journey of a book is defined well before it’s printed, so choosing and understanding the target audience during the process is a good starting point. In 2018, during a harsh debate around the legalisation of abortion, Argentinian Tamara Goldenberg and Martina Perosa published the photozine Mamarazzi with Frente Editorial Abierto (Open Publishing Front).The Front’s approach to publishing focuses on dissident publications in form of photozines, whose price can be a maximum of 3% of the minimum wage. For more information: https://frenteeditorialabierto.com.ar/ By appropriating images and texts used by a widespread gossip magazine to celebrate motherhood, they revealed the subliminal propaganda behind it. In addition to the use of easily recognisable materials, the next step they took to reach their audience was to distribute the publication in hairdresser shops around the Palace of the Argentine National Congress in Buenos Aires.Photobook lovers can only download a free pdf. The printable version can be found here: https://drive.google.com/file/d/10-UGC_U5qXm67B_4EMGjysXiNkKrk_y_/view.

Rebel with a cause

Photobook history shows an extensive use of the medium to support or criticise political stances and trigger discussions on urgent issues.Critic Gerry Badger has long been collecting and studying propaganda and protest photobooks, a selection of which was exhibited in 2017 during the Photobook Phenomenon exhibition in Barcelona. A chapter about the topic can be found in the catalogue: VVAA. 2017. Argentinians Sebastián Pani and Belén Grosso developed Y un Día el Fuego (And One Day the Fire), a project about women burned by their partners in a country that suffers a new victim of gender violence every 30 hours.A pdf version of the publication is available here: https://goo.gl/iKqkRE In addition to telling painful stories of survivors, the resulting publication, made possible by Buenos Aires-based platform Turma, also serves as a guide for women to understand how gender violence works and how to denounce it before it’s too late.Julieta Escardó founded Turma in 2016. After running the first photobook fair on the continent since 2001, when fotolibro the Spanish translation of ‘photobook’ didn’t exist yet, she realised that to help spreading photobook culture, other activities were necessary. More can be learned here: http://somosturma.com/ With 3,000 copies printed, it’s being used for informational talks that raise awareness and offer legal advice. On a different level of political engagement, the work of Mexican designer and publisher León Muñoz Santini fits with André Breton’s declaration: ‘One publishes to find comrades!’This declaration was made by André Breton in 1920, quoted by Gareth Branwyn, Jamming the Media: A Citizen’s Guide Reclaiming The Tools of Communication, Vancouver: Chronicle Books, 1997 His publishing house, Gato Negro, prints very affordable and densely political publications from different genres and authors.Gato Negro. https://www.gatonegro.ninja These pamphlets, poetry, illustrations and photobooks are united by their sharp and often ironic criticism of politics, violence, migration policies, economics and other deformations of power.

Let’s read photobooks to our children before bed

Making the youth familiar with this format is another long-term path we can start walking right now, like the itinerant library of CdF, which brings photobooks to different educational institutions, or the image-editing and photobook-making workshops for children led by Claudia Tavares and Rony MaltzA video summary of the activities can be viewed here: https://www.ateliedaimagem.com.br/curso/maos-a-obra-brincando-com-fotos-e-livros/ in Rio de Janeiro. Besides fostering an early connection with the format, playfully analysing photographic narratives helps in the forming of a critical attitude towards the images that have been pervading our daily lives since childhood.A brief log of CdF's activities can be consulted here: Montevideo Center of Photography. 2019. Mobile Book Library. http://cdf.montevideo.gub.uy/articulo/mediateca-movil

Photobooks won’t be viral or mainstream. Instead, they’ll be patiently waiting on the shelves to be browsed over time. The challenge is getting to those shelves and offering more opportunities for impact. Like sowing seeds, if we want to create a sustainable environment for photobooks, hands need to get dirty, and grains must be selected according to the soil. And the harvest, if we work well, won’t be ours.